Case Studies

Every drop of water is different, and our experiences with health and enviornments are just as unique. These case studies focus on specific areas, but illustrate the variety and compelxity of global water issues.

The United States is in the midst of an ongoing natural gas boom, spurred by advancements in horizontal drilling and slick water hydraulic fracturing—otherwise known as “fracking.”

Fracking has been a popular subject for debate among politicians and environmentalists, and while it does pose a certain risk to public health and the environment, it’s not worse than other fossil fuels produced in America: coal (21% of national production) and petroleum (28%). Of course, all of these options are less sustainable and more corrosive than renewables like wind and solar.

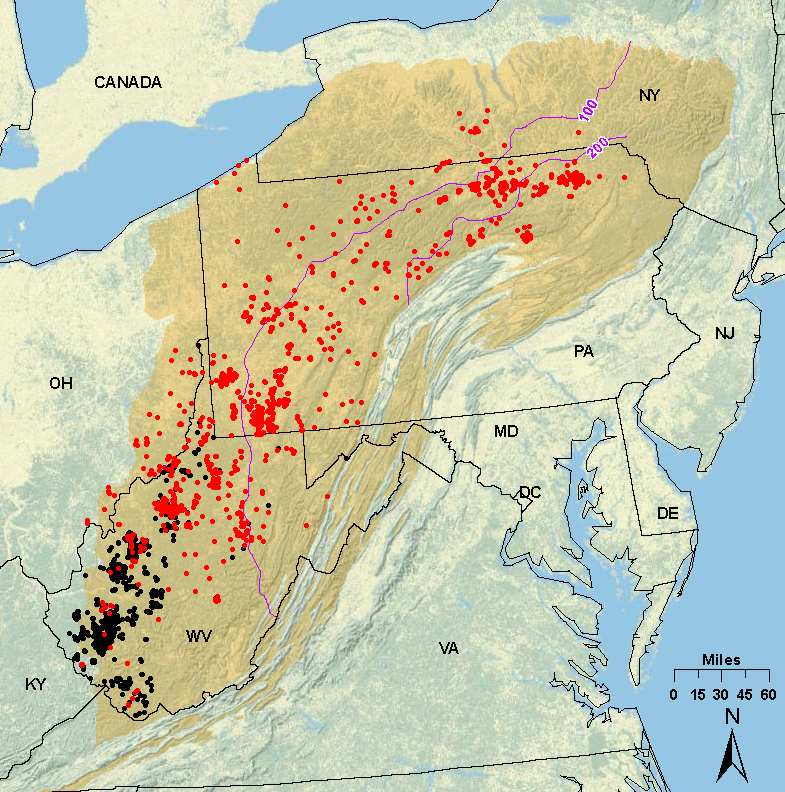

One of the largest reserves of natural gas is the Marcellus Shale formation that spans New York, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia. This layer of bedrock contains natural gas that can be extracted by injecting specialized fluids into the subterranean shale to release gases which rise to the surface through steel-lined wells.

A single well can tap into shale deposits that span hundreds of acres by drilling horizontal holes that stretch away from the initial well like spokes on a wheel. The shale tapped by this process is 5000-9000 feet underground, which is actually far-removed from any groundwater in the area (around 200 feet underground).

After “fracking fluid” is pumped into the ground to release natural gas, the fluid returns to the surface, where it is difficult to dispose of and is usually just stored in large metal tanks—or, sometimes, in giant pits lined with plastic. Even if just a fraction of these storage sites result in leaks or spills, their environmental impact can be hazardous—such as in Butler, PA where 840 gallons of wastewater was spilled in 2013.

There are 7788 active wells in Pennsylvania, and while a state law requires wells to be located 300 feet from surface water supplies, it’s not surprising that accidents happen. From 2008-2012 the Scranton Times-Tribune found 161 homes, farms, and churches with “damaged water supplies” [source and above]. In addition to contamination from wastewater, abandoned wells have been know to release methane gas from deep underground, which contributes to global warming and paranoia-inducing reports of flammable water.

Call your representatives and tell them to invest in renewable energy instead of natural gas. It’s a bit of a struggle because natural gas is widely available with existing technology, and it creates jobs that pay $20,000 more than the average Pennsylvania salary

Find out if there are any gas wells in your area, and be watchful for reports of water contamination. Last year, the water supplies of 22 Cities in Pennsylvania were found to contain potentially dangerous amounts of chromium-6, a carcinogen linked to a medley of cancers. While thought to be naturally occurring, chromium-6 can also be a waste product of various industries. The contamination is more severe than the threshold enforced in California (while still being below the national level) and requires reverse-osmosis water filters to remove from drinking water. Stay vigilant Pennsylvania!

The Mar Menor one of the bigger coastal lagoons from Europe and the Mediterranean. A sandy bar, called La Manga, acts as a barrier between the lagoon and the Mediterranean Sea, creating a hypersaline coastal lagoon on the Southeast side of the Iberian Peninsula, It is crossed by five, more or less functional, channels or “golas”. (Perez-Ruzafa, 1996).

Unforunately, the Mar Menor is one step away from collapse by pollution. Symptomatic proliferation of toxic algae throughout the Murcia region has led the local Ministry of Health to ask the Spanish government for urgent and constant monitoring. But the reaction comes 18 years after the first warnings. The situation is limited, according to the Spanish Institute of Oceanography and the University of Murica. The Prosecutor's Office has opened an investigation into the actions of the Hydrographic Confederation of Segura, the Executive, farmers and municipalities.

While the high turbidity of the water (murkiness due to suspended particles) is a clear problem, the massive presence of phytoplankton implies severe degeneration of a unique ecosystem included in the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands of International Importance (the Deposited Unesco) and protected as a natural area and area of special interest.

The Mar Menor lagoon has ecological characteristics of high productivity and biological diversity as a result of being separated from the Mediterranean Sea by a 22 km long (100 m to 1,200 m wide) sand bar. Designated by the United Nations as a “Specially Protected Area of Mediterranean Importance”, the coastal lagoon has been, however, vulnerable to eutrophication due to the rise in population along the coast and use of fertilizers for agriculture.

"The main problem occurs when these cells (unicellular algae) produce toxins that can affect both the marine organisms that ingest them as shellfish or fish, as people who consume them or simply breathe the atmosphere where there have been" warns the Ministry of Health in its report on toxic phytoplankton along beaches of Murcia.

The causes of high pollution are manifold, but the principal cause, according to the health report, is accumulation of organic waste produced by agricultural and urban waste. Further seepage of underground nitrates, increasing aquaculture, action lines in the maritime environment, climate change and other natural sources compound the problems. The main culprits: the agricultural model and continued demand for water.

Murcia orchard has become a bottomless pit of use of water resources. It is estimated that there are 20,000 hectares of irrigated land that officially surveyed. The wells, deeper each year, have joined the proliferation of private desalobradoras: 300 registered; 700, according to a study; and more than 1,000 according to other estimates.

Farmers pour desalted brine and other wastes into the boulevards that reach the lagoon by the action of the rains. At the same time, water with fertilizer and water with excess nutrients seep into the subsoil. According to Miguel Angel Esteve, professor of Ecology and Natural Areas Management at the University of Murcia, these actions attributed to 60% of the excessive contribution of nitrates and phosphates, with concentrations have increased by 50 in two decades. Esteve also notes that the degradation of surrounding wetlands prevents them from properly filtering the lagoon, and must be addressed in the comprehensive regeneration plan.

Although the Spanish government now considers regeneration of the Mar Menor “a priority”, scientific and academic institutions have had 18 years of warning about the problem (Lloret, Marín, Marín-Guirao,2008). The Ministry of Health recognizes in the report that calls for a continued and urgent plan of surveillance, there have been episodes of toxicity in spring and summer since 2006.

10 years ago, between 8 and 9 July, fifty people "needed medical assistance [for] throat infection symptoms, bronchospasm, hoarseness, dysphonia, eczema and skin erythema" in three beaches. The cause was a proliferation of marine vegetation and Chattonella Gymnodinium types, "both producing neurotoxins that cause the symptoms described". A year later, in April 2011, and last summer, there was once again observed a high density of microalgae. Detected in 2015, 20 kilometers of Eagles, an epidemiological outbreak that led 95 people to suffer respiratory and allergic conditions.

Lloret, J.; Marín, A.; Marín-Guirao L. (2008). Is coastal lagoon eutrophication likely to be aggravated by global climate chage? Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science nº 2, (Vol. 78). Academic Press. pp: 403-412.

Pérez-Ruzafa, A. (1996).The Mar Menor, Spain. In: Morillo, C. and González, J.L. (Ed.). Management of Mediterranean Wetlands. Case Studies 2 (Vol. 3). Ministerio de Medio Ambiente. MedWet. Madrid. pp: 133-155.